Aviation Mysteries of the North - Chapter Excerpt

Chapter Six

A Cold Winter Morning

November 30, 1945

A Cold Winter Morning

November 30, 1945

Lieutenant (jg) John McMillan had his jacket collar turned up around his neck as a barrier against the biting, cold wind blowing across the airfield at Kodiak, Alaska. He tried not to hurry and look intimidated by the weather, keeping his hands inside the pockets of his worn leather jacket and cursing himself for leaving

his gloves and cap back at the hangar. It was only a short distance to the Flight Operations Office to check the weather conditions, but halfway across the tarmac he regretted not dressing more appropriately. Now that the wind was hitting him square in the face on his walk back to the aircraft, it felt even colder, numbing

his exposed cheeks and causing his eyes to water.

A dark, early morning ceiling of low clouds was masked behind the bright lights of the hangars on the southern edge of the airfield. The sun was still well below the horizon and the winter moon was once again hidden above a thick blanket of gray overcast. Weather conditions were not expected to improve. Snow

flurries were forecast by early afternoon with winds increasing to as much as 40 knots. By evening the clouds would be thinning, but the winds would be increasing further, gusting to 50 knots.

It was a good time to be heading home, Lieutenant McMillan thought as he opened the hangar door and stepped inside. The warm air from the powerful overhead heaters hit him immediately, enticing him to open his jacket in relief. In another hour his seven man crew and cargo of seventeen passengers would be

safely over the Gulf of Alaska, on their way home to Washington State and their waiting families. For most of the servicemen it was their first trip stateside since the war ended, finally being furloughed in time for Christmas. For others it was a chance at a well deserved rest before returning for duty, or in the case of the flight crew, another routine mission back to waiting wives and girlfriends at Whidby Island Naval Air Station, north of Seattle.

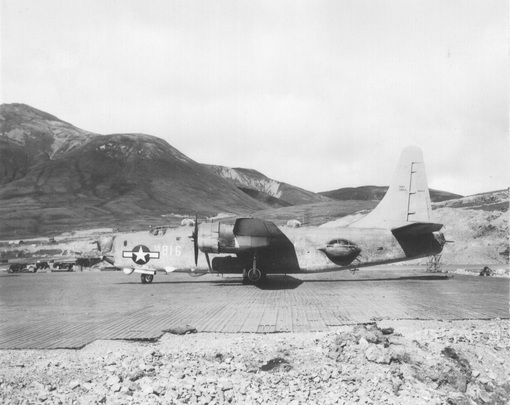

A four-engine PB4Y-2 Privateer patrol bomber stretched over half the width of the large hangar as Lt. McMillan entered, completely enclosed from the winter weather inside the painted walls and interlocking sliding doors. Another identical aircraft scheduled for the mission was parked further back at an angle on the opposite side of the hangar. A few mechanics and technicians from the late shift were scattered throughout the building, finalizing various repairs and inspections.

McMillan’s crew was thankful for the available space, which allowed their daily maintenance and preflight checks to be conducted in relative comfort before the mission. A third PBY Privateer was

parked in an identical hangar nearby, their crew preparing for the same flight across the Gulf of Alaska. Other aircraft were sitting outside on the parking ramp and taxiway, waiting for repairs or their own crews for later missions.

Hangar space was not always available, especially during the winter months, and aircraft were often left outside and preheated using large, portable Herman Nelson style heaters. The main wheeled body of the heaters was heavy, but attached with lightweight, flexible hoses, much like the tentacles of an octupus,

which could be easily positioned for distributing heat in various locations on the aircraft. Because of the Privateer's large wings and fuselage, a minimum of three heaters were usually required, one near each wing for heating the engines and a third for warming the interior cabin and cockpit.

parked in an identical hangar nearby, their crew preparing for the same flight across the Gulf of Alaska. Other aircraft were sitting outside on the parking ramp and taxiway, waiting for repairs or their own crews for later missions.

Hangar space was not always available, especially during the winter months, and aircraft were often left outside and preheated using large, portable Herman Nelson style heaters. The main wheeled body of the heaters was heavy, but attached with lightweight, flexible hoses, much like the tentacles of an octupus,

which could be easily positioned for distributing heat in various locations on the aircraft. Because of the Privateer's large wings and fuselage, a minimum of three heaters were usually required, one near each wing for heating the engines and a third for warming the interior cabin and cockpit.

All three aircraft assigned to the flight were Navy PB4Y-2 Privateers, a derivative of the Army Air Force B-24 Liberator used for high altitude bombing. In outward appearances the B-24 and PB4Y-2 were very

similar, except for some minor structural modifications and internal configurations. Most noticeable was the twin or forked tail of the B-24 being replaced with a larger single vertical tail on the Navy PB4Y-2. The

Navy version also had a longer nose section enclosing a ball turret, a second top turret behind the wings and side fuselage turrets in place of open machine gun windows for a heavier defensive capability.

similar, except for some minor structural modifications and internal configurations. Most noticeable was the twin or forked tail of the B-24 being replaced with a larger single vertical tail on the Navy PB4Y-2. The

Navy version also had a longer nose section enclosing a ball turret, a second top turret behind the wings and side fuselage turrets in place of open machine gun windows for a heavier defensive capability.

Normal armament was twelve .50-caliber machine guns. Additional radio and radar antennas also gave the Privateer an improved search capability. Internally the Privateer contained more electronic systems and crew space than a B-24, as well as additional fuel tanks in the bomb bays necessary for long range patrol. The four Pratt & Whitney engines had also been modified with higher power ratings for

lower level flight requirements, including replacing the turbo superchargers on B-24 Liberator engines with mechanical superchargers on the Privateers. A bomb load of 12,800 pounds could be carried if necessary, although with a decreased fuel range. The aircraft had a top speed of 247 mph at a maximum ceiling

of 19,500 feet and a maximum range of 2,900 miles. It carried up to twelve crewmembers while on normal patrol missions, but a lesser number when configured as a transport.

The three Privateer crews were not concerned with long range patrols on November 30, 1945.

World War Two was over and each of their aircraft had since been modified to carry additional passengers in place of bombs and armament. The crews were more than happy providing transportation for their fellow

servicemen heading home. Most had been busy for months flying passengers back and forth from Kodiak, but seats were still a luxury. One of the lower ranking Navy men on base had been trying for days to get a flight stateside where he could be released from active duty, but available space was always filled with

higher priority passengers. Circumstances changed the young man’s fate when a Coast Guard Lieutenant overheard his predicament and graciously gave up his own seat, deciding instead to fly on a later commercial flight.

Lt McMillan glanced at his watch, noting the time as 5:20 am as he began briefing the other seven members of his crew on the in-flight weather conditions and their intended route from Kodiak to Seattle, Washington. They would be the first of three PB4Y-2s scheduled to depart, carrying seventeen active duty

passengers on the nine hour instrument flight. The other two Privateers would depart at timed intervals behind them, each carrying their own full load of passengers. There were no questions from the crew. Each of them knew their duty assignment and could perform each others’ tasks almost as well as their own. They were an experienced crew, used to long range war patrols over the North Pacific, but still adapting to peacetime duties. The passenger flights were, if anything, a welcome change...

lower level flight requirements, including replacing the turbo superchargers on B-24 Liberator engines with mechanical superchargers on the Privateers. A bomb load of 12,800 pounds could be carried if necessary, although with a decreased fuel range. The aircraft had a top speed of 247 mph at a maximum ceiling

of 19,500 feet and a maximum range of 2,900 miles. It carried up to twelve crewmembers while on normal patrol missions, but a lesser number when configured as a transport.

The three Privateer crews were not concerned with long range patrols on November 30, 1945.

World War Two was over and each of their aircraft had since been modified to carry additional passengers in place of bombs and armament. The crews were more than happy providing transportation for their fellow

servicemen heading home. Most had been busy for months flying passengers back and forth from Kodiak, but seats were still a luxury. One of the lower ranking Navy men on base had been trying for days to get a flight stateside where he could be released from active duty, but available space was always filled with

higher priority passengers. Circumstances changed the young man’s fate when a Coast Guard Lieutenant overheard his predicament and graciously gave up his own seat, deciding instead to fly on a later commercial flight.

Lt McMillan glanced at his watch, noting the time as 5:20 am as he began briefing the other seven members of his crew on the in-flight weather conditions and their intended route from Kodiak to Seattle, Washington. They would be the first of three PB4Y-2s scheduled to depart, carrying seventeen active duty

passengers on the nine hour instrument flight. The other two Privateers would depart at timed intervals behind them, each carrying their own full load of passengers. There were no questions from the crew. Each of them knew their duty assignment and could perform each others’ tasks almost as well as their own. They were an experienced crew, used to long range war patrols over the North Pacific, but still adapting to peacetime duties. The passenger flights were, if anything, a welcome change...